Dragon Claws

A growing sense of disparity has started to appear in monetary policy strategy, with major European central banks starting to tilt dovish while their U.S. counterpart, the Federal Reserve, remains cautious about easing rates too soon.

Central banks on both sides of the Atlantic had moved together in the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic to battle inflation by embarking upon the most aggressive monetary policy tightening cycle in decades and flooding the economy with ample liquidity.

But with inflation having significantly come down from its 2021 and 2022 highs across the globe, interest rate cuts have now become the expectation. European countries have been able to move much faster in that regard than the Fed, with Switzerland paving the way and becoming the first major economy to cut rates in March.

Earlier this week on Wednesday, Sweden joined Switzerland after the Riksbank cut its key policy rate by 25 basis points.

The Bank of England (BoE) also issued its latest rate decision on Thursday. The BoE maintained interest rates at a 16-year high, though two members of its monetary policy committee voted to cut by 25 basis points. Moreover, Governor Andrew Bailey hinted that the BoE may cut rates faster than markets expect.

Meanwhile, the European Central Bank (ECB) is widely anticipated to lower rates in June, as inflation has come back down to its 2% target and growth has remained muted across the Eurozone.

Recent commentary from the Fed, in contrast, has remained on the cautious side. Though chair Jerome Powell surprised markets with his dovishness at his last press monetary policy press conference, remarks from Fed speakers since have continued to call for a “wait-and-watch” attitude.

“For the foreseeable future, the main question that will continue to loom over central banks on both sides of the Atlantic is how to avoid premature celebrations of victory over inflation, holding interest rates high for a sufficiently long time to gain greater confidence that inflation is moderating, but not for so long as to slow economic growth,” the Council on Foreign Relations, an independent think tank, had said in a blog post earlier in February.

Following the Riksbank’s rate cut on Wednesday, Deutsche Bank looked into historical trends to see which central bank follows which during coinciding monetary policy easing cycles.

“The potentially imminent European easing cycle has raised some eyebrows in terms of timing and how much they can cut before the Fed start their own easing cycle,” Deutsche Bank’s Jim Reid said.

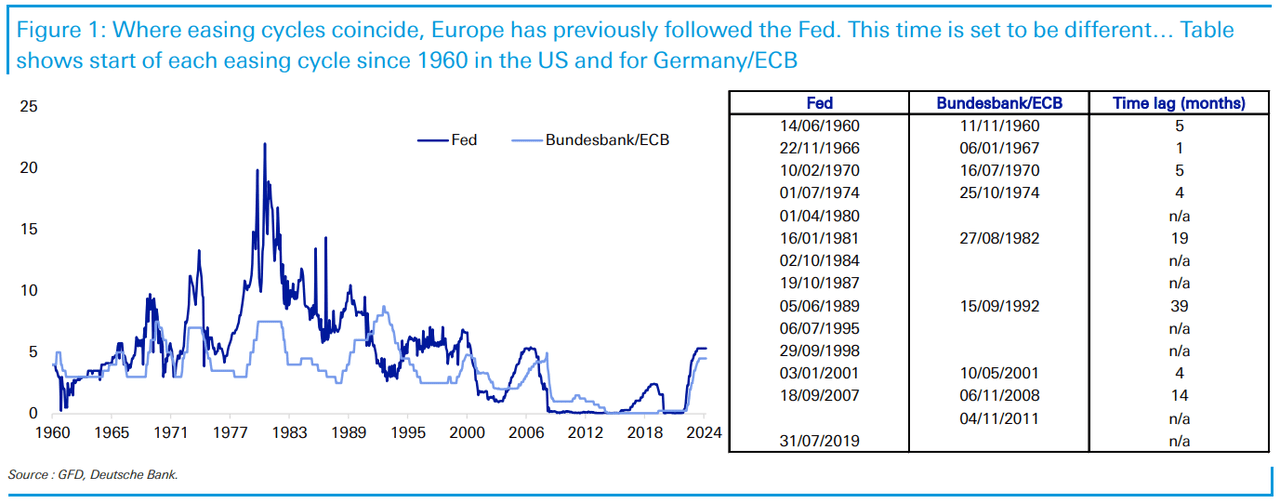

The following Deutsche Bank chart shows the Fed Funds versus the German Bundesbank rate before 1999 and the ECB rate spliced in thereafter. The table to the side shows the dates of the start of easing cycles in both regions over the last 65 years, and calculates the lag between the two.

“(The chart) highlights that over this period, the Bundesbank/ECB have not eased before the Fed, apart from in 2011 when the ECB cut rates due to the Sovereign crisis when the Fed was already at zero and didn’t cut rates further. Outside of that period … the Fed has had more easing cycles and where they coincide, they have always previously been the first to cut,” Reid said.

“So assuming the ECB does cut rates next month as expected, and the Fed remains on hold for at least the next several months before easing, it will be a unique event in modern times,” Reid added.

More on monetary policy

Source link