Not for the first time, the IMF and World Bank annual meetings last week coincided with increased volatility in financial markets. It is almost as if people talking about financial exuberance, fractured geopolitics and a fragile global economy make investors take fright. The Vix index — Wall Street’s “fear gauge” — hit its highest level since April late in the week before recovering to a more normal level by Tuesday.

The proximate cause of increased fear in the financial system was revelation of exposure among US regional banks to the recent failures at car parts maker First Brands and auto lender Tricolor amid accusations of fraud. The wider concern was that these were just examples of wider credit excess that demonstrated that the world had moved into a much more dangerous zone of what is loosely called the regulatory cycle.

History tells us that large financial crises almost always result in a regulatory backlash to prevent the damage being repeated. But over time, the new financial rules tend to be viewed as an overreaction and are loosened as institutional memories of the crisis fade. The welcome results of financial deregulation prompt more of it until a light touch system allows financial excess and brings the next crisis.

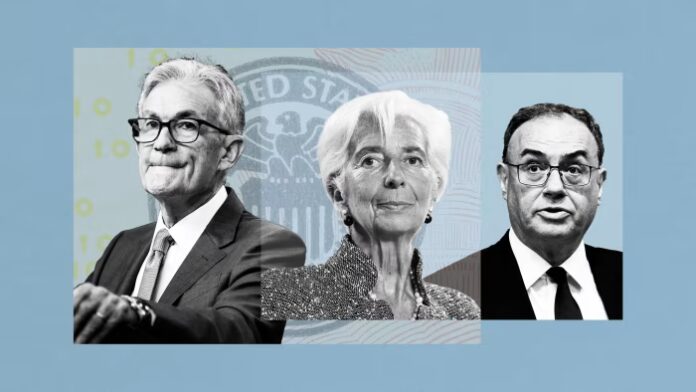

While a fundamental rule of the central banks club is not to criticise each other, leading members are now branching out in different directions when it comes to their financial stability mandates.

Not standing together

Despite the revelation of significant credit losses in regional banks, US regulators and the Trump administration are focused on relaxing financial regulations to boost growth. In a demonstration that not every aspect of central banking is independent of government (nor should it be), earlier this month Federal Reserve vice-chair for supervision Michelle Bowman interviewed US Treasury secretary Scott Bessent, in which he said that banking regulations needed to be eased because the “regulatory framework that was developed post Dodd Frank is too tight”.

When Bowman got the job of vice-chair for supervision, it was specifically on a ticket of deregulation, lowering its burden on smaller US banks, decreasing regulatory buffers of capital required and moving to a lighter touch regime. “Driving all risk out of the banking system is at odds with the fundamental nature of the business of banking,” she said. The chart below shows the extent to which the US is lowering bank capital requirements, according to consultants Alvarez & Marsal.

Of course, not everyone in the US, or even within the Fed, agrees with the Trump administration’s approach. In a thinly-disguised warning about the changes, Fed governor and former vice-chair for supervision Michael Barr described the regulatory cycle and its ability to encourage financial crises in a July speech. A key lesson, he said, was that “policymakers should resist the pressure to loosen regulations or to refrain from imposing regulation on new activities during the boom times”.

Other central banks are also grappling with political pressure to loosen regulation, not least the Bank of England. Just last week it relaxed post global financial crisis regulations on bankers’ bonuses, allowing them to receive incentive payments faster. “These new rules will cut red tape without encouraging the reckless pay structures that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis,” said Sam Woods, head of the BoE’s Prudential Regulation Authority, rather hopefully.

In an important speech earlier in the month, governor Andrew Bailey acknowledged he felt pressure to loosen financial regulations to avoid having the “stability of the graveyard” in the UK economy. He acknowledged that many of the political challenges to the regulatory system suggested that rules had “overdone it post-crisis”, but rejected the argument that financial regulation had led to lower productivity growth. His message was don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater and adapt regulations carefully. That must be correct, but it is a difficult balance to strike.

Christine Lagarde sells a tougher message. In complete contrast to Bessent and Bowman, who say that bank regulations should be relaxed because business is shifting towards private credit markets, the president of the European Central Bank argues that policymakers adapt rules “not by lowering standards for banks, but by levelling them up for non-banks that are involved in bank-like activities, or with significant links to the banking sector”.

Attitudes to financial stability in central banking have rarely been so diverse.

An imminent crisis?

Whether it matters that financial regulators don’t see eye-to-eye depends partly on the degree of risk there is in the financial system. The IMF annual meetings last week were a good time to take stock.

The IMF’s global financial stability report pulled few punches. Risks were “elevated” it said, with stretched asset prices, governments ever deeper in debt and vulnerabilities in private credit markets.

US equities were particularly exuberant, with forward price-earnings ratios in the 96th percentile of value since 1990 unlike those in other advanced economies and emerging markets where they were roughly average. The IMF said the chart below might exaggerate the US vulnerability, but more sophisticated models of US equity valuations still put them in the 81st percentile.

The boom in artificial intelligence investment is clearly a potential trigger for financial stability risk stemming from an equity crash that would substantially weaken broad markets such as the S&P 500.

But the big concern of the IMF this year was the increasing exposure of banks to hedge funds and private credit in the non-bank financial institution sector. While growth in this area is prompting the US to loosen regulation on banks, the fund sees substantial risk because banks already tend to have sizeable exposures to hedge funds and private credit. Indeed, this is what blew up in the US regional banking sector last week.

Lenders with non-bank exposures worth more than their capital now represent more than 40 per cent of total banking assets, the IMF said, with a few banks holding non-bank exposures more than five times their capital.

Adding to these signs of financial vulnerability is clear evidence of global financial fragmentation, stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a loosening of financial ties between the US and China. This reduces the efficiency of finance, raising the chance of financial crises and making it harder to mount co-ordinated responses when crises occur, according to the latest annual “Geneva Report”, published on Monday.

The big question is where we are in the regulatory cycle. Although you can never quite know, there is little doubt that memories of the global financial crisis are fading, pressures to loosen financial regulations are intense and many central banks are working hard to justify looser controls.

We seem to be in the loosening part of the cycle but not yet in the deep complacency part. The IMF, for one, is nothing like where it was in April 2006, when it published its global financial stability report, saying “the near-term outlook is ‘as good as it gets’, or some would say, maybe even better than that”.

We should be thankful for that at least.

What I’ve been reading and watching

-

Former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram Rajan is worried that central bank policy easing will end in tears

-

The most arresting statistic in IMF week was that the fund is projecting that US gross debt as a share of GDP will be higher than that of Greece by 2028. No wonder the IMF thinks the US should act

-

It seems like officialdom in the UK are finally willing to say clearly that Brexit has hurt the UK economy, with governor Bailey and the chancellor speaking out

-

Relationships between the ECB and its staff union are sinking even further

One last chart

No one knows for certain, but punters are betting that Kevin Hassett will become the next Fed chair when Jay Powell’s term ends in May 2026. Trading on this question has been volatile on Polymarket, but Fed governor Christopher Waller’s odds have been slipping back as he has not shown a willingness to be ridiculously dovish. Kevin Warsh finds it difficult to hide his hawkish tendencies, and being dovish is thought to be a pre-requisite for a Trump nomination.

Since insider trading is not really policed on these markets, expect them to move sharply once a decision has been taken, but before it is announced.

Source link