The airstrikes have stopped. Surviving Israeli hostages have been released and returned to their families, while hundreds of Palestinians in Israeli prisons have been returned to theirs.

How and when the rest of Donald Trump’s Mideast deal unfolds isn’t entirely clear. In the past few days, there have been moments when it seems this tentative agreement could still unravel — yet in an era when conflicts seem endless, even a tenuous peace deserves some fanfare.

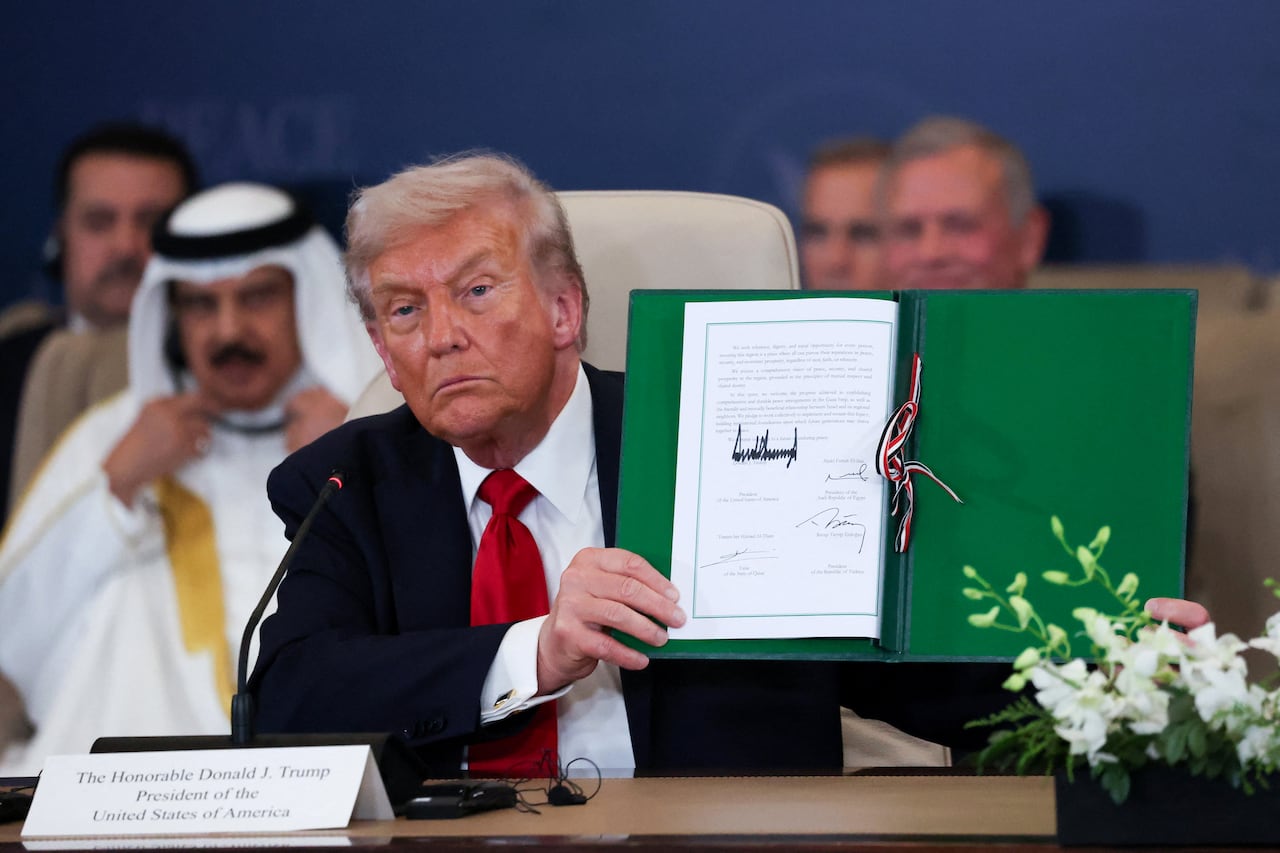

But to declare an end to the two-year Gaza war, as Trump did Tuesday, as the “historic dawn of a new Middle East” wildly overstates what the ceasefire deal delivers.

Though it has, for now, stopped the bloodshed in a particularly violent and painful conflict in the Middle East, this is just one episode in what is a decades-long dispute that remains largely unsolved.

What the Trump deal has delivered, for the moment, is a classic example of a “negative peace” — the absence of violence — without addressing many of the conflict’s underlying causes.

In his extensive public comments in the region earlier this week, Trump did very briefly acknowledge the long history of division in the Middle East, insisting that “for the first time anyone can remember, we have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to put the old feuds and bitter hatreds behind us.”

He cited Israel’s blows against Hezbollah and Iran, the intended disarming of Hamas, as well as the Abraham Accords (which saw four countries in the region sign unprecedented normalization agreements with Israel in 2020) as further evidence of the beginning of a peaceful “new” Middle East.

But Trump did not articulate a clear plan for attempting a negotiated, lasting settlement between Israelis and Palestinians. Vague statements in his 20-point deal promised the U.S. would establish dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians aimed at “a political horizon for peaceful and prosperous coexistence” and at “changing mindsets … by emphasizing the benefits that can be derived from peace.”

In fact, Trump refused to comment about a two-state solution to the conflict — the preferred outcome for previous U.S. administrations. When reporters asked him about it, he said: “A lot of people like the one-state solution. Some people like the two-state solution. So we’ll have to see.”

The future of a two-state solution

Once at the heart of U.S. policy on the conflict, the two-state solution appears to have been written out of the American vision for the Middle East, putting the U.S. at odds with many world leaders and Western countries, including Canada — which recently recognized a Palestinian state.

Trump’s plan did indicate that once certain requirements of the Gaza deal are fulfilled, “the conditions may finally be in place for a credible pathway to Palestinian self-determination and statehood, which we recognize as the aspiration of the Palestinian people.”

But beyond that brief mention, such aspirations were largely left out of Trump’s deal.

CBC News chief correspondent Adrienne Arsenault asks Monk School of Global Affairs founding director Janice Stein to break down what’s know about the negotiations behind U.S. President Donald Trump’s Gaza peace deal.

The peace plan “was put together where one of the two parties to the [wider] conflict, the Palestinians, have no voice,” Nader Hashemi, associate professor of Middle East politics at Georgetown University, told CBC News. “It was largely an Israeli peace plan that was drawn up with the Trump administration and input from Arab dictators.”

On the prospect of a comprehensive regional peace, Hashemi added: “This is not the plan that is going to get us there.”

What will get us there?

Finding a plan to “get there” — to get a lasting peace between Israelis and Palestinians — has eluded even the most determined U.S. presidents.

Even before the Oct. 7, 2023, attack and the ensuing two-year Israeli bombardment of the Gaza Strip, life in the Middle East was marked by a legacy of failed peace negotiations: repeated cycles of violence, stalled Israeli-Palestinian talks, and the absence of any concerted effort to restart dialogue.

To get beyond a cessation of hostilities, entrench real change and perhaps achieve a “positive peace,” trusted brokers are needed to pressure and persuade all sides to come to the table — and intense diplomacy and incentives are required to encourage compromise on the more intractable differences. Think Good Friday Agreement, the 1998 peace deal that ended the violence in Northern Ireland.

Such ground-shifting peacemaking can take years to come to fruition. In the Middle East right now, pursuit of that kind of “positive peace” appears to be on the backburner and an ever-more-distant prospect.

In a statement after the summit in Egypt, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney mildly countered Trump’s sweeping characterization of the deal and appeared to acknowledge that ending two years of violence cannot solve decades of regional conflict.

“The road to stability and peace remains long,” he’s quoted as saying in a statement.

“But this [deal] is a vital first step.”

Source link