:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/GettyImages-2237923655-0340e689fa1943e88187fd2ccede988d.jpg)

Key Takeaways

- Economists say the flurry of policies aimed at forcing drug companies to lower prices may not be as effective as President Donald Trump intends.

- Tariffs are likely to push up prices, including for generic medications and products made in the U.S.

The Trump administration has issued a flurry of orders aimed at lowering pharmaceutical prices, but experts are leery that the actions will achieve that goal.

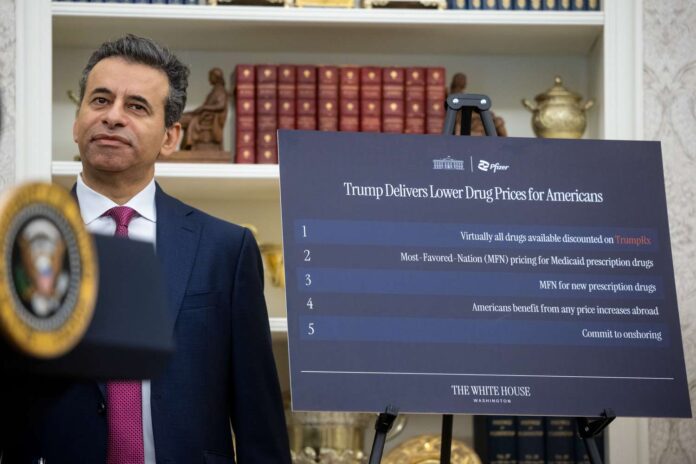

The latest move in Trump’s ongoing campaign to reduce drug prices came late last month when the White House announced a deal between the government and Pfizer (PFE), the multinational company that makes COVID-19 vaccines, Viagra, and other widely used products.

Under the deal, which could serve as a model for agreements with other major manufacturers, the company will sell its products to Medicaid at prices on par with those offered to other developed countries. In addition, the company will offer medications directly to consumers at a discount on Trumprx.gov, a website scheduled to launch in 2026. In return, the company will be exempt from the punishing 100% tariffs Trump is threatening to impose on pharmaceutical imports.

The deal appears to address a longstanding complaint from Trump and U.S. consumer advocacy groups: the sticker prices for many drugs are significantly higher in the U.S. than in Europe. In some cases, drugs that cost thousands of dollars in the U.S. are available for low cost or for free to Europeans. For example, in 2021, a single injection of the arthritis drug Humira cost American patients $3,000, when a generic version was available in Germany for $10, according to reports.

How This Affects Your Finances

If you’re currently paying steep prices for brand-name drugs, President Donald Trump’s policies aimed at reducing pharmaceutical prices are unlikely to lower them much, according to experts.

Pricing Controls Won’t Change Much in the U.S.

The pricing controls Pfizer agreed to harken back to an executive order Trump issued in May. The order required that government health agencies, including Medicare and Medicaid, purchase drugs at no higher a cost than Most-Favored-Nation pricing—that is, at a price comparable to other developed countries. That’s significant because the government is the largest buyer of drugs in the country through its Medicare and Medicaid health insurance programs.

However, drug pricing is notoriously complicated, making it easy for companies to obscure what customers are actually paying. In the U.S. and Europe alike, most drugs are not sold directly to consumers, but through insurance companies and other middlemen, who often receive various discounts and rebates that may not be reflected in the list price.

After all is said and done, Medicaid already pays similar prices for drugs as its European counterparts, making it unlikely that the MFN policy will change much, said Geoffrey Joyce, an economist and director of the Schaffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California.

“Although the MFN policy correctly captures the urgency of addressing unaffordable U.S. drug prices, it is unlikely to meaningfully reduce prices due to legal, operational, and market barriers,” Harvard professors Amar H. Kelkar and Edward R. Scheffer Cliff wrote in an editorial for the Journal of the American Medical Association in July.

The Most-Favored-Nation pricing could eventually influence the costs of newly introduced drugs, pushing down prices in the U.S. and raising them in Europe, Joyce said. That could start to happen in the next three to five years, he estimated.

In the meantime, the industry can use a multitude of tactics to keep its profit margins intact.

For example, in circumstances where drug prices would actually have to be lowered, pharma companies may instead just stop offering their drugs in foreign countries. Darius Lakdawalla, chief scientific officer at the USC Schaeffer and Dana Goldman, founding director of the USC Schaeffer Institute for Public Policy and Government Service, wrote in an op-ed.

“Facing a choice between deep cuts in their U.S. pricing or the loss of weakly profitable overseas markets, we can expect many firms to pull out from overseas markets at their earliest opportunity, leaving U.S. consumers with the same prices, pharmaceutical manufacturers with lower profits, and future generations with less innovation,” they wrote. “In sum, everyone loses.”

Trump RX Duplicates Private Companies

The direct-to-consumer portal is also unlikely to change much, Joyce said.

Only about 10% of people buy prescription drugs directly rather than through insurance. Other companies already offer discounted drugs directly to uninsured consumers, including GoodRx and the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Company, so it’s unclear what advantage the government-run store will have over its private counterparts.

Tariffs Could Push Up Prices

If Trump implements pharmaceutical tariffs as promised, the import taxes would likely drive up prices, economists said.

In a social media post last month, Trump said the tariffs would be set at 100%, and would only affect “branded” drugs, seemingly exempting generics, which account for 90% of the drugs sold in the U.S.

Even without the new tariffs, existing Trump tariffs on India and China could still push up drug prices.

Prices will gradually rise as stockpiles run out and contracts are renegotiated, economists at ING said in a commentary. Prices for generic drugs from India are expected to eventually rise 25%, they wrote. Prices on domestically manufactured products could also rise, as many manufacturers source their ingredients from other countries.

Big, Beautiful Bill Undermines Medicare Price Negotiations

Another factor contributing to the rise in drug prices was tucked away in the massive tax and spending legislation known as the “Big Beautiful Bill,” which Trump signed into law in August.

The bill includes a provision allowing drug companies to exempt more products from the Medicare price negotiations put into place by former President Joe Biden’s administration. The BBB allows more drugs to be considered “orphan drugs” that treat previously untreated conditions.

Joyce said this provision undermines an avenue of drug price reduction that was actually poised to push prices down somewhat.

Source link